Load XDP programs using the ip (iproute2) command

Nota bene: If you don’t even know what XDP is, continue reading I will explain it later.

My journey

Past week I was working on a piece of software that needed the ability to define some custom network paths to route HTTP traffic to multiple destinations based on rules defined on a data store.

During the first phase, I had the opportunity to go through different ideas, and since my end result needed to be very fast and able to handle high throughput, in my mind there was only one thing “XDP”. I already used XDP in the past working at a similar project and my knowledge about eBPF was already good enough that my team agreed this was crazy and thus we decided we should try.

I’m aware of, and I usually use iovisor/bcc or libbpf directly, but this time, I wanted something I can use to validate some ideas first, debug some of that code and only later include my program in a more complete project.

Even if usually pay a lot of attention to LKML, lwn.net and in general, to relevant projects in this area like Cilium I didn’t know that the ip command was able to load XDP programs since last week when I was lucky enough to be in man 8 ip-link looking for something else and I found it! However, using it in that way wasn’t really straightforward (for me) and I had to spend quite some time to put all the pieces together so I decided to write this walkthrough.

Wait wait wait.. What is XDP?

From the iovisor.org website:

XDP or eXpress Data Path provides a high performance, programmable network data path in the Linux kernel as part of the IO Visor Project. XDP provides bare metal packet processing at the lowest point in the software stack which makes it ideal for speed without compromising programmability. Furthermore, new functions can be implemented dynamically with the integrated fast path without kernel modification.

Cool, so XDP is a way to hook our eBPF programs very close to the network stack in order to do packets processing, encapsulation, de-encapsulation, get metrics etc..

The important thing you need to know is that you can write a program, that gets loaded into the kernel as if it was a module but that can be loaded without modifying it.

This kind program is called an eBPF program and is compiled to run against a special VM residing in the kernel that verifies and then executes those programs in a way that they cannot harm the running system.

Note that eBPF programs are not Turing complete, you can’t write loops for example.

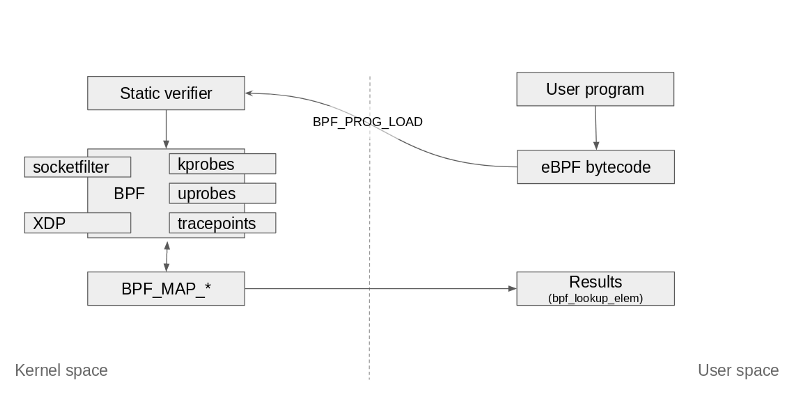

You can look at the diagram below to visualize how the loading of eBPF programs works.

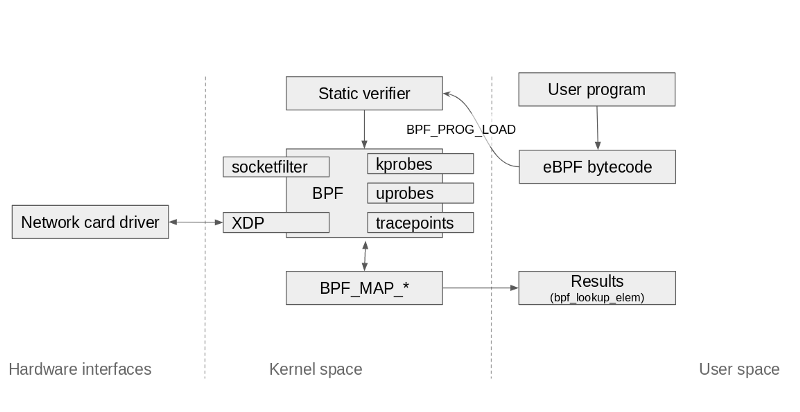

Said all of that, XDP programs are a specialized kind of eBPF programs with the additional capability to go lower level than kernel space by accessing driver space to act directly on packets.

So if we wanted to visualize the same diagram from an XDP point of view it will look like this.

In most cases, however your hardware may not support XDP so you will still be able to load XDP programs using the xdpgeneric driver so you will still get the improvements of doing this lower level but not as with a network card that supports offloading network processing to it instead of doing that stuff on your CPU(s).

If this is still very unclear you can read more about XDP here.

What can I do with XDP?

This depends on how much imagination you have, some examples can be:

- Monitoring of the network packet flow by populating a map back to the userspace, look at this example if you need inspiration;

- Writing your own custom ingress/egress firewall like in the examples here;

- Rewrite packet destinations, packets re-routing;

- Packet inspection, security tools based on packets flowing;

Let’s try to load a program.

Requirements:

You will need a Linux machine with Kernel > 4.8 with clang (llvm ≥ 3.7) , iproute2 and docker installed. Docker is not needed to run XDP programs but it is used here because of three reasons:

- Docker by default creates bridged network interfaces on the host and on the container when you create a new container. Sick! I can point my XDP program to one of the bridged interfaces on the host.

- Since it creates network namespaces, I can access them again using the

ipcommand, since we are talking about that command here, this is a bonus for this post for me. - I can run a web server featuring cats, the real force that powers the internet, and then I can then block traffic using XDP without asking you to compile, install or run anything else.

Step 0: Create a docker container that can accept some HTTP traffic

So, let’s run caturday, we are not exposing the 8080 port for a reason!

# docker run --name httptest -d fntlnz/caturday

Step 1: Discover the ip address and network interface for httptest

Obtain the network namespace file descriptor from docker

# sandkey=$(docker inspect httptest -f "{{.NetworkSettings.SandboxKey}}")

Prepare the network namespace to be inspected with the ip command so that we can look at its network interfaces without using docker exec .This also allows us to use any program we have in our root mount namespace against the container’s network. This is needed because the image we used fntlnz/caturday does not contain iproute2.

# mkdir -p /var/run/netns

# ln -s $sandkey /var/run/netns/httpserver

Don’t worry too much about that symlink, it will go away at next reboot. Now, let’s show the interfaces inside the container:

# ip netns exec httpserver ip a

Output

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000 link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00 inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever71: eth0@if72: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state UP group default link/ether 02:42:ac:11:00:02 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 0 inet 172.17.0.2/16 brd 172.17.255.255 scope global eth0 valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

The IP address is 172.17.0.2.

Our interface eth0 in the container has id 71 and is in pair with if72 so the ID in the host machine is just 72, let’s get the interface name in the host machine.

# ip a

Cool, the name is right there:

72: vethcaf7146@if71: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue master docker0 state UP group default

So I have: IP: 172.17.0.2, Interface name on the host: vethcaf7146

Step 2: Generate some traffic to go to the interface we just created with the container httptest

For this purpose, we can use hping3 or the browser or even curl. In this case I will be using hping3 because it continuously sends traffic to the interface and I can see how this changes after loading my XDP program.

# hping3 172.17.0.2 --fast

In another terminal open tcpdump to see the packet flow.

# tcpdump -i vethcaf7146

vethcaf7146 is the name of the interface we found at step 2.

Step 3: Compile an XDP program using clang

Let’s take this XDP program as an example (there’s a more complete example later!)

#include <linux/bpf.h>

int main() {

return XDP_DROP;

}

Compile it with:

$ clang -O2 -target bpf -c dropper.c -o dropper.o

Once loaded, this program drops every packet sent to the interface. If you change XDP_DROP with XDP_TX the packets will be sent back to the direction where they came from and you then change it to XDP_PASS, the packets will just continue flowing.

XDP_TX can also be used to transmit the packet to another destination if used after modifying the packet’s destination address, mac address and TCP checksum for example.

Step 4: Load the dropper.o program

At the previous step, we compiled dropper.o from dropper.c. We can now use the ip command to load the program into the kernel.

# ip link set dev vethcaf7146 xdp obj dropper.o sec .text

The careful reader may have noticed that we are using the xdp flag in the previous command. That flag means that the kernel will do its best to load the XDP program on the network card as native. However not all the network cards support native XDP programs with hardware offloads, in that case, the kernel disables that.

Hardware offloads happen when the network driver is attached to a network card that can process the networking work defined in the XDP program so that the server’s CPU doesn’t have to do that.

In case you already know your card supports XDP you can use xdpdrv, if you know that It doesn’t you can use xdpgeneric .

Step 5: Test with traffic and unload

At this point, after loading the program you will notice that your tcpdump started at Step 3 will stop receiving traffic because of the drop.

You can now stop the XDP program by unloading it

# ip link set dev vethcaf7146 xdp off

Step 6: Drop only UDP packets

For the very simple use case we had (drop everything) we didn’t need to access the xdp_md struct to get the context of the current packet flow, but now, since we want to selectively drop specific packets we need to do that.

In order to do that, however, we need to declare a function that has xdp_md *ctx as the first argument, to do that we need to use a different section than .text when loading our program, let’s see the program below:

#include <linux/bpf.h>

#include <linux/in.h>

#include <linux/if_ether.h>

#include <linux/ip.h>

#define SEC(NAME) __attribute__((section(NAME), used))

SEC("dropper_main")

int dropper(struct xdp_md *ctx) {

int ipsize = 0;

void *data = (void *)(long)ctx->data;

void *data_end = (void *)(long)ctx->data_end;

struct ethhdr *eth = data;

ipsize = sizeof(*eth);

struct iphdr *ip = data + ipsize;

ipsize += sizeof(struct iphdr);

if (data + ipsize > data_end) {

return XDP_PASS;

}

if (ip->protocol == IPPROTO_UDP) {

return XDP_DROP;

}

return XDP_PASS;

}

char _license[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

Wow, a lot changed here!

First, we have a macro that allows us to map a section name to specific symbols, then we use that macro in SEC(“dropper_main”) to point the section name dropper_main to the dropper function where we accept the xdp_md struct pointer. After that, there’s some boilerplate to extract the Ethernet frame from which we can then extract the information related to the packet like the protocol in this case that we use to check the protocol and drop all the UDP packets (line 26).

Let’s compile it!

$ clang -O2 -target bpf -c udp.c -o udp.o

And now we can verify the symbol table with objdump to see if our section is there.

objdump -t udp.o

udp.o: file format elf64-little

SYMBOL TABLE:

0000000000000050 l dropper_main 0000000000000000 LBB0_3

0000000000000000 g license 0000000000000000 _license

0000000000000000 g dropper_main 0000000000000000 dropper

Cool, let’s load the function using the section dropper_main always on the same interface we used before vethcaf7146.

# ip link set dev vethcaf7146 xdp obj udp.o sec dropper_main

Nice! So let’s now try to do a DNS query from the container to verify if UDP packets are being dropped:

# ip netns exec httpserver dig github.com

This should give nothing right now and dig will be stuck for a while before exiting because there’s our XDP program that is dropping packets.

Now we can unload that program and our DNS queries will be there again

# dig github.com

;<<>> DiG 9.13.3 <<>> github.com

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 49708

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 2, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1</pre>

; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 512

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;github.com. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

github.com. 59 IN A 192.30.253.112

github.com. 59 IN A 192.30.253.113

;; Query time: 42 msec

;; SERVER: 8.8.8.8#53(8.8.8.8)

;; WHEN: Sun Oct 07 23:10:53 CEST 2018

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 71

Conclusions

When I first approached eBPF and XDP one year ago I was very scared and my brain was telling sentences like

I’m not going to learn this you fool!! ~ My brain, circa June 2017

However, after some initial pain and some months thinking about it I really enjoyed working on this stuff.

But! As always I’m still in the process of learning stuff and this topic is very exciting and still very very obscure for me that I will surely try to do more stuff with this low-level unicorn.

I hope you will enjoy working with XDP as much as I did and I hope my post here helped you going forward with your journey, as writing it did with mine.

I love this! ~ My brain, circa October 2018

Following, some references for you.

References

- https://github.com/iovisor/bpf-docs

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JRFNIKUROPE

- https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/latest/networking/af_xdp.html

- https://cilium.readthedocs.io/en/latest/bpf/

- https://suricata.readthedocs.io/en/latest/capture-hardware/ebpf-xdp.html?highlight=XDP

- https://www.netdevconf.org/2.1/slides/apr6/bertin_Netdev-XDP.pdf

Thanks for reading! You can find me on Twitter and on GitHub.